A Monmouth shop and gallery owner turned flood damage into an impromptu art event, laying out water-marked pieces on her steps with a handwritten sign: “soggy art work for sale.” Jenny Chuter, who runs businesses in the town, said the flood reshaped the work in unexpected ways and gave it fresh character. “The flood damaged pieces took on a new life so I put them on the steps and a sign saying ‘soggy art work for sale’,” she said. The sale drew attention to the creative resilience that small businesses often show after severe weather. It also raised a wider question for high streets under pressure: how do independent traders keep trading and keep spirits up when water rises and stock suffers?

The sale took place in Monmouth, Monmouthshire, Wales, in November 2025, according to WalesOnline.

Turning flood damage into a creative moment

Chuter treated the watermarks, ripples and stains as part of the story. She gathered affected pieces and set them out on the steps outside, inviting passers-by to see the work with fresh eyes. Her approach reframed the damage. Rather than hide the impact, she leaned into it and sparked curiosity. People often pause when they see a bold sign and a clear idea. The phrase “soggy art” catches the ear and the eye, and it delivers a simple pitch: these pieces look different now, but they still hold value and meaning.

Artists and gallerists often talk about the role of chance in the creative process. Floodwater can alter paper fibres, create tide lines, smear ink, and shift pigments. Those changes can ruin a piece or transform it. In this case, Chuter chose to show the results rather than bin them. Her decision reduced waste and gave the work a second life. It also sent a message that art can carry marks of time and place, including a sudden downpour and rising water in a riverside town.

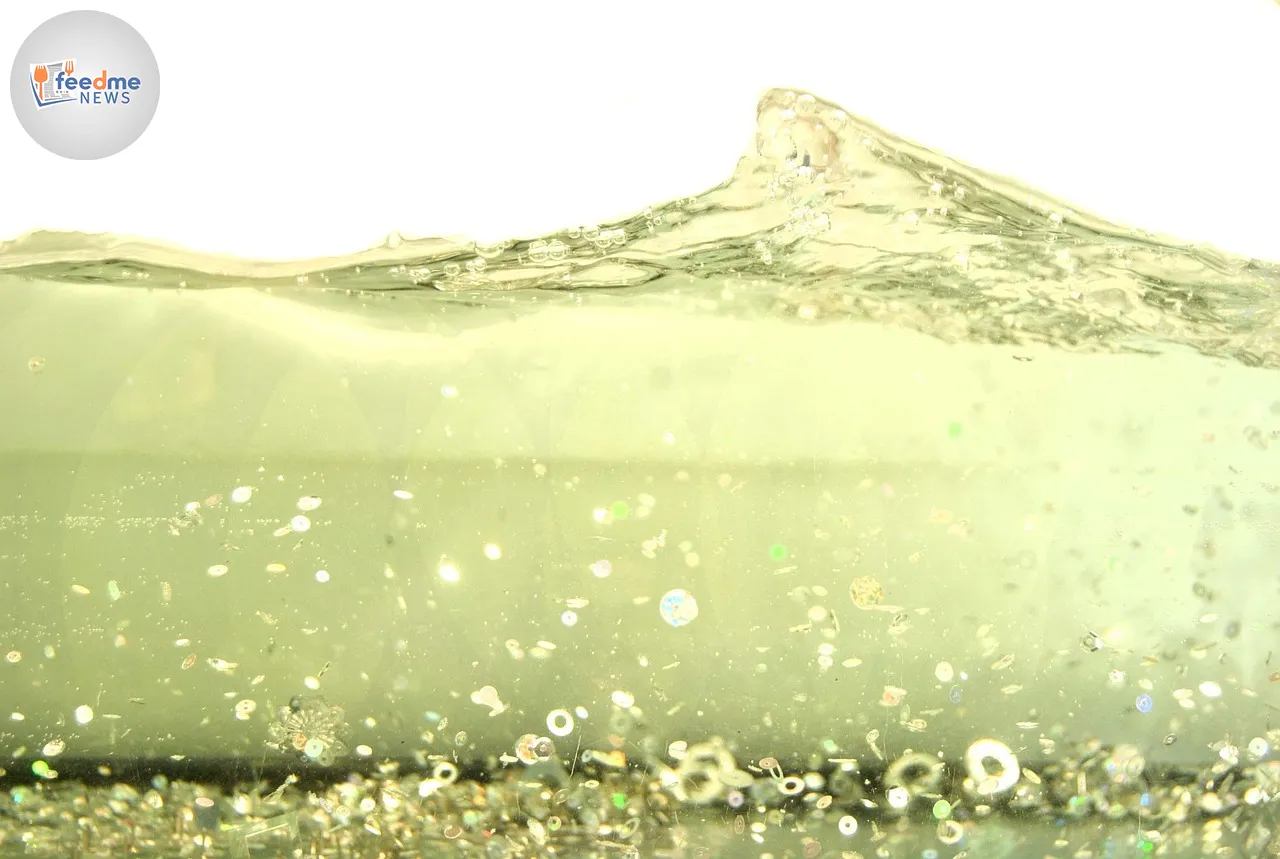

Monmouth’s rivers and the reality of flood risk

Monmouth sits at the confluence of the Rivers Wye and Monnow, a striking location that also carries flood risk. Heavy rain can swell both rivers and push water over banks and across low-lying streets. People in the town know the routine: watch the forecast, check levels, move stock, and mop floors when water creeps under doors. The setting draws visitors and supports a lively high street, yet it also demands constant readiness when storms track in from the west.

Authorities and agencies monitor river conditions and issue guidance when levels rise. In Wales, flood risk management includes river gauges, alerts, and advice for communities. Local traders plan around that guidance, and they often adapt layouts and storage to lift goods off the floor. Even with preparation, floods can still reach shelves and frames. A gallery faces extra risk because paper, card, canvas, and wooden stretchers react to moisture. Once water hits those materials, the damage can spread fast.

Small businesses face hard choices after water damage

When water gets in, independent shops and galleries face a tough list of tasks. Owners clean floors, dry walls, and sort stock. They fix fixtures and fittings and check electrics before they invite customers back in. They also need to decide what to save, what to salvage, and what to sell at a discount. That process takes time, especially for small teams that run on tight margins. Every hour on clean-up means an hour away from sales, yet the work still needs doing.

A gallery holds pieces that artists have consigned or that the owner has bought. Each item carries both creative and commercial value. Water complicates both sides. Some damage can wipe out value. Other marks can nudge a piece into a different category: imperfect, experimental, or unique. By selling “soggy” pieces in the open, Chuter showed a quick route through that dilemma. She created a clear channel to move affected work, free up space, and keep a sense of momentum on the street.

When water reshapes art: damage, texture, and perception

Conservators note that water can cockle paper, lift glazes, swell frames, and cause mould if owners do not dry items quickly. Pigments can bleed and inks can feather. Those changes usually count as damage. Yet some collectors enjoy the trace of time in an object. In art history, viewers often value patina on metal, craquelure in old varnish, or the worn edge of a print pulled from a well-loved press. Flood marks do not fit neatly in that list, but they can still shift perception.

Artists also experiment with chance effects. Some use water, smoke, oxidation, or weathering as part of the process. While a flood comes without consent, its marks still act on materials. Chuter’s choice to show the results invited people to see those effects and judge them. That invitation matters. It turns a setback into a conversation about process, material, and meaning. It also helps the public understand what water does to art and why some pieces may change forever.

A circular approach: salvage, reuse, and less waste

Disasters often lead to piles of waste. Damaged goods leave shops and enter skips. A “soggy art” sale pushes in a different direction. It keeps material in circulation and reduces disposal. In simple terms, reuse saves resources and cuts the carbon cost of replacement. A small, street-level effort will not solve the waste problem on its own, yet each act of salvage sets a useful example. It shows how local traders can make practical, low-cost decisions that cut loss.

The idea also aligns with a broader shift in retail. Many independent shops now favour repair, refill, and reuse. A gallery can take part in that shift by selling studio seconds, test prints, or damaged stock with clear labels. Buyers make informed choices, pick up a story along with the object, and support local trade. Chuter’s move fits that pattern. She told a clear story about what happened to the work and why it still deserved a place on someone’s wall.

High street visibility and the power of a clear message

Independent businesses often rely on footfall and word of mouth. A simple sign on a step can capture both. It signals honesty, draws a crowd, and invites a quick look. People stop, point, and chat. That small moment can lead to a sale now or a visit later. In a historic market town like Monmouth, where the high street mixes food, books, art, and daily essentials, visible ideas help shops stand out and keep a sense of community alive.

A public display also helps rebuild rhythm after disruption. Floods drain energy and slow trade. An open-air rack or a step-side table sends a different signal: we keep going. That message can help nearby traders as well, because activity on one doorstep often spills across to the next. In a compact town centre, small sparks of interest can link up and restore a buzz after a hard spell of weather.

Coverage and context: what we know

WalesOnline reported the “soggy art” sale on 16 November 2025 and identified the owner as Jenny Chuter, who runs businesses in Monmouth. The report set out how she framed the flood’s impact and how she presented the work on the steps with a clear sign. Those details paint a picture of quick thinking and open communication. They also give a snapshot of life for traders who balance creative work with day-to-day retail demands.

Beyond that, the event highlights a familiar pattern in towns with riverfront streets. People accept the risk that water brings and build in ways to cope. They raise stock, plan for alerts, and look for ways to recover faster after each event. The “soggy art” sale fits within that pattern. It shows practical action, local knowledge, and humour in the face of disruption. It also shows how a single idea can carry through a difficult week and keep customers engaged.

Chuter’s “soggy art” sale offers a small but striking lesson in resilience. She faced flood damage and chose to meet it in public,